Heritage

Where It All Began

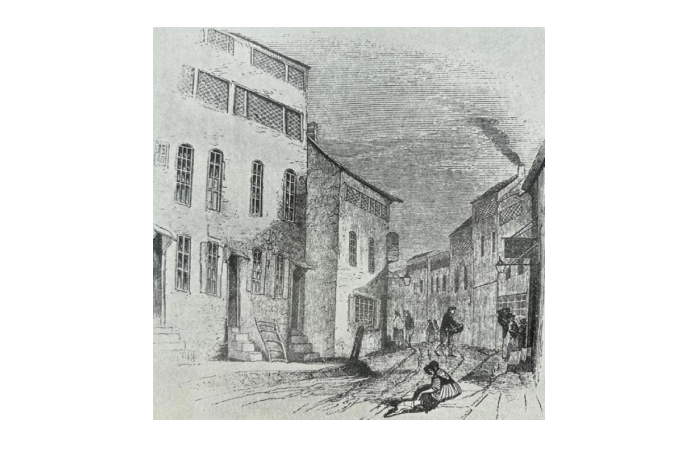

The remarkable story of Warner begins within the heritage of the 16th century Huguenot scarlet dyers, who in 1685 escaped persecution and the Edict of France fleeing to Spitalfields in London. The legacy of the Warner family included substantial links within the silk weaving business and also that of printing and fustian dyeing at The Old Ford in Middlesex. Benjamin Warner (1828-1908), a descendent of this group, worked alongside his mother and in 1839, when Benjamin was aged eleven, they took over the business of his father, a Jacquard loom harness maker and card cutter. The entrepreneurial Benjamin could see wider business prospects, so when in 1857 the opportunity arose for him to purchase the business, designs and workshop of Alphonse Brunier, he seized this with both hands. This purchase offered him an exclusive customer list and a good cache of designs to reproduce. His knowledge of weaving was such that he was able to produce some of the complicated patterns that Brunier himself had been unable to weave.

Specialising in silk

In 1867, Benjamin then went into partnership with William Folliott. Folliot brought to the partnership an outstanding knowledge of design and card cutting for a more varied array of silk cloths. Although this partnership only lasted two years, Warner and Folliott were to cross paths again when Benjamin purchased the business of Daniel Walters of Braintree. In March 1870, a formal company was set up and business commenced between Mr B Warner and Mr C Sillett and in 1871 Mr W.C Ramm joined. Warner offered silk wovens, Sillett offered tapestries and braids, with Ramm selling chintzes. Warner was the majority shareholder and saw to it that any business could be supplied. He specialised in the highest quality figured silks, and for one hundred years the firm wove silk patterns alongside special commissions. They mainly produced silks for the furnishing trade, occasionally weaving for ceremonial robes and dress fabrics.

Notable designers

Although the firm was noted for its traditional patterns, it also engaged with several notable designers of this time, such as Owen Jones, E.W. Godwin, G.C. Haite, Bruce Talbert, A H Mackmurdo, Sidney Mawson, Arthur Silver (of the Silver Studio) G.R Kennerley and Lewis F Day. Their designs reflected the type of patterns that typified the Arts & Crafts, Aesthetic and Modern eras. The few extant customer records for this period in time show that Jones’s designs were woven for Jackson & Graham, Talbert’s for Waring & Sons, Haite’s for Lengyon & Morant, Mawson’s for Liberty’s and Silver’s patterns were used for the wedding trousseau of Princess May (later Queen Mary). In 1874 Mr Sillet retired, dying ten months later. From 1878, a new regime for the firm led to them supplying in equal measure both woven and printed cloth under the business of Warner, Ramm & Stanway; Stanway left in 1879 to pursue his own interests but left the legacy of his patterns with Warner. Printed fabrics were becoming increasingly popular for curtains and upholstery for all, including the wealthiest of homes. The firm outsourced the manufacturing, with the designs in many cases being owned by, or exclusive to, Warner & Ramm. This partnership was to last until 1891, when both parties went their separate ways, with Ramm leaving the patterns at the factory that Warner owned.

Exhibition achievements

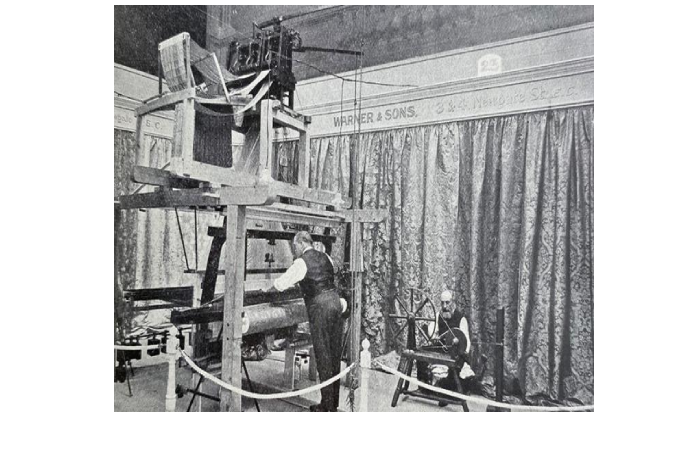

By 1900, the firm was considered the foremost furnishing silk weavers in Britain having won major awards at both national and international manufacturer exhibitions. At both the 1900 and 1912 The Earls Court Exhibition for the Silk Association of Great Britain, and The Empire, the firm installed a fully working Jacquard loom, alongside a substantial display of their wares.

Acquisition of rivals

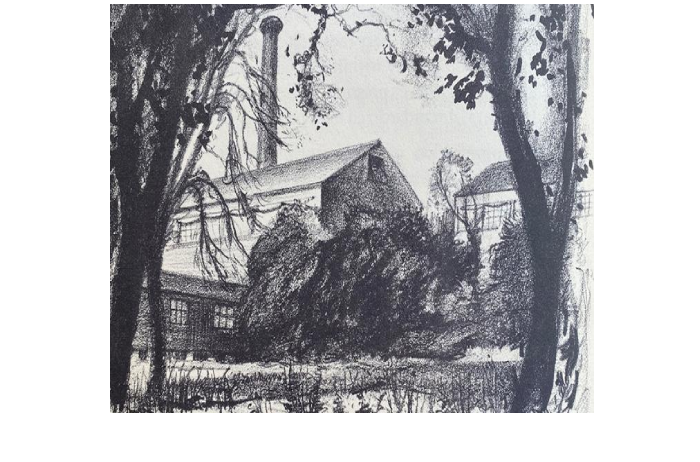

From an important business perspective, Warner acquired its two major rivals. The first, in 1885, was Charles Norris & Co, whose previous acquisition had been Daniel Keith & Co. Both Norris and Keith produced designs in the Gothic revival style, supplying woven and printed patterns to Crace & Son for A. W. N Pugin’s newly built Palace of Westminster. Norris’s position as supplier of traditional silk and velvets to the Royal Household was transferred to Warner through the purchase. The second crucial purchase was that of Daniel Walters & Sons, who also supplied to the British Royal Household as well as many other European Royal Households. Walters also purchased many designs from Owen Jones, Bruce Talbert and William Folliott, the latter of whom redrew some of the patterns which were to become significant within the British Royal Household. They too had won medals at exhibitions, with the most memorable being at the 1894 Royal Society of Arts where Daniel Walters won gold, and Daniel Keith silver. Warner’s acquisition in 1894 comprised of the looms, patterns and premises; New Mills in Braintree was one of the largest silk weaving complexes in the country. By 1910 Warner had closed their Bethnal Green factory and transferred all but a handful of cottage weavers (who wove silk velvet and tissues) to New Mills.

Presence at coronations

In 1891, a partnership was formed between Benjamin and his two sons, Alfred, aged 35 and Frank, aged 29, with the firm becoming Warner & Sons. Frank inherited his father’s interests in silk weaving and so in 1907, upon his father’s failing health, the future direction of the firm fell to him, and in 1915 he became sole owner. Up until this point the firm had continued to weave high quality silk cloth for events and significant people of patronage. The biggest and most auspicious is that the firm has woven articles for every single Coronation since 1902. The Coronation of Edward VII & Queen Alexandra saw the looms weaving velvets and silk satins which were to be embellished with solid gold thread embroidery, as well as the sacred Cloth of Gold. The tradition of the Cloth of Gold for the monarch’s pallium and supertunica dates back to the time of Edward I. The most recent Coronation of 1953 saw the firm opening its mill to the public to show the weaving for this historic event. The firm wove all the velvets, the Cloth of Gold, the panelling for Westminster Abbey, the damask for the thrones and all seating within the Abbey, the silk for the main carriages, as well as the silk caddy for Queen Elizabeth II’s overdress which was used for the anointing ceremony.

Frank Warner

The twentieth century saw Frank Warner (1862-1930) actively promoting better design education and continuing his father’s passion for promoting the silk industry. In 1919, during his tenure as managing director, he introduced power weaving into the workshops. He produced innovative weaving methods for making figured silk velvets culminating in a patent in 1914 for three pile silk velvets, a fabric constructed of three heights of silk pile. The traditional patterns continued to be supplied to the various governmental offices including The Office of Works, the Foreign Office and the Palace of Westminster, where new designs were introduced for the ministerial offices by the in-house design team of Herbert Woodman and Bertrand Whittaker. Alongside the established clientele of the Royal Household, Cowtan & Sons, Harland and Wolfe placed an order for Neo- Classical silk for the ill-fated RMS Titanic. The firm also supported the Arts & Craft business of Morris & Co, helping to fulfil their orders. Eminent and newly emerging interior designers of the age were added to the order books, including Nancy Lancaster, Edith Wharton, Sibyl Colefax, Lady Sackville, Cecil Beaton, John Fowler, Syrie Maugham and Basil Ionides, to name a few.

Expansion into America

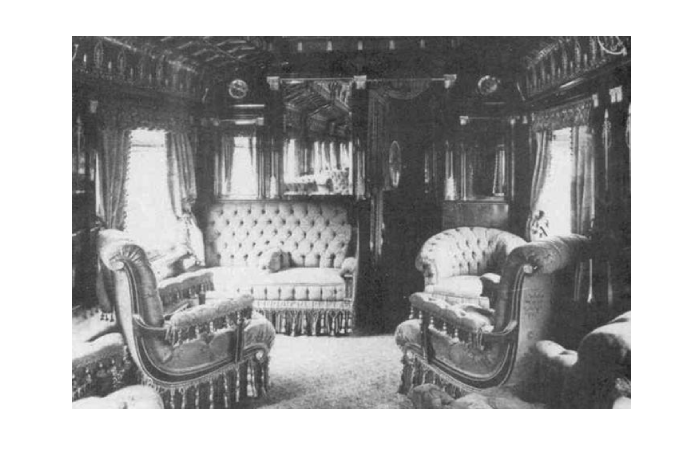

When it received an endorsement by The Roosevelt Administration, the Warner brand seized upon the opportunity of exposure in America. In 1901, Warner set up an American division, opening a New York Office at Broadway and Twenty Second Street, an area known as the ‘Ladies Mile’. It did this in order to supply for the 1902 refurbishment of The White House, where amongst its order was a Neo-Classical style silk woven for the curtains. American customers included private commissions for the Vanderbilts, Elsie de Wolfe, the Astors, Rose Cumming, and Elsie McNeill Lee, as well starting to supply textile convertors, such as Frederic Schumacher. Schumacher encouraged the firm to open a showroom and offices in Paris, his native country, and they did just this in 1919. Huge orders were received from the Railroad Company Pullman Inc. for its ‘1st Class Cars’, opulent carriages that criss-crossed the straits of America allowing wealthy American businessman to live for months at a time in splendour.

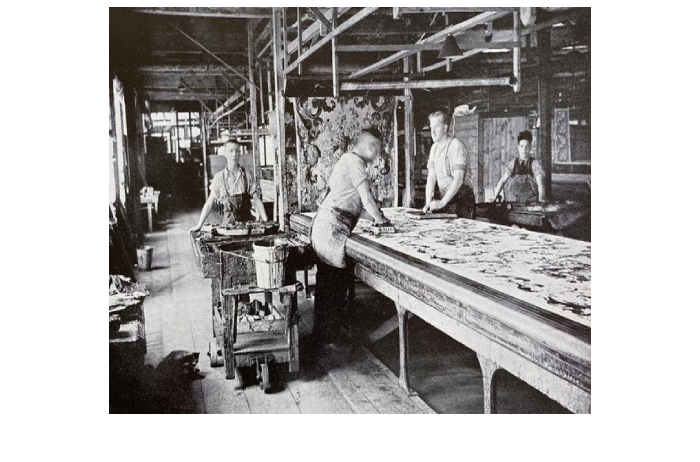

Printworks Introduction

The divisive economic and social conditions of the start of the twentieth century saw the Spanish Influenza (1918-20) and the Great Depression (1920-21) both of which greatly impacted the production of cotton cloth in America. This affected the textile industry, which saw an increase of customers looking for cheaper cloth which was printed, rather than woven. Warner took the decision to purchase a block print workshop in Dartford from the firm Newman Smith & Newman (1926). Newman Smith & Newman had struggled, losing a large number of experienced block printers to influenza and experiencing the increasing cost of exported cotton. Purchasing the factory and equipment alongside its order book, they introduced ‘modern designs’ alongside traditional floral patterns. Designs were printed for new customers such as Marion Dorn Ltd, with a scarf she designed produced for the American charity The Royal Oak. Cunard, owner of The RMS Queen Mary, featured wovens by Alec Hunter, prints by Marion Dorn, and a tapestry by Walter Crane, which had previously wowed the visitors at the 1908 British Franco Exhibition.

Growth under Goodale

An elderly Sir Frank Warner appointed his energetic son-in law Ernest Goodale (1896-1984) (later Sir) to the board, becoming Managing Director in 1930. He served on The Board of Trade and Governmental Committees during the 2nd World War, having previously fought in the 1st World War as a 2nd Lieutenant of the 9th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment serving in Mesopotamia and with Dunsterforce. His military exposure saw him run a very effective business, where he was very highly thought of by employees and customers. He continued the Warner tradition of promoting good design education through The Council of Industrial Design and The Royal Society of Arts. To accompany the stock range of cloths that were woven, he strove to increase the design and manufacture of more forward-thinking fabric products and he employed the maverick Alec Hunter (1899-1958) as a chief designer in 1932. In the same year, Goodale introduced hand screen printing at the Dartford factory which was to propel the company into the new age of technical printing and lasted until they ceased printing in 1939. It was the onset of the 2nd World War and the continuing social and economic world struggle that forced the company to close the business, moving production to external manufacturers.

World War II provision

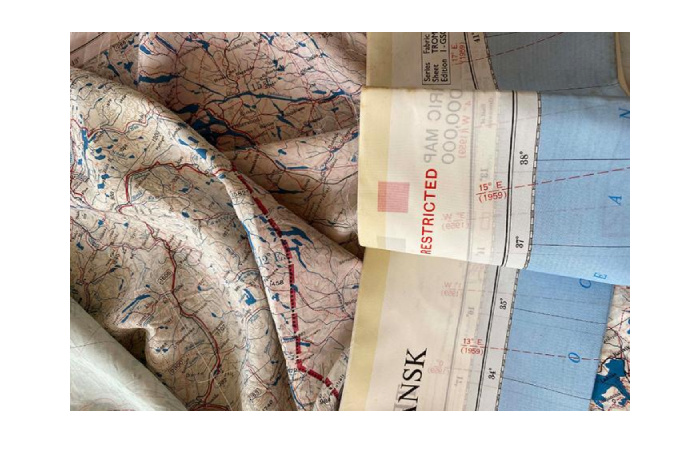

Hunter’s use of modern fibres within the power loom weavings and foresight in purchasing freelance designs from both British and French Design Studios spearheaded the firm’s development and growth. He opened the company up to a newer, diverse customer base, including furniture manufacturers and retailers such as Gordon Russell Ltd, Fortnum and Mason, and Dunn’s of Bromley, who sold the fabrics and cushions by Theo Moorman. Special sound enhancing cloths were sold to Marconi Wireless Telegraph for their speakers. Major projects included The Royal Institute of British Architects headquarters (1934), The University of London Senate House (1938), the Forum Cinema Complex in Coventry (1934), The United States Embassy in London (1928-1939) and St John’s College Cambridge (1940). The 2nd World War saw the firm providing utility fabrics designed by Enid Marx (of the War Office), as well as silk cartridge bags for ammunition, parachute silk and secretive commissions of lightweight silk which became maps for The Special Operations Executive (which later formed into MI5 and MI6). The controls and restriction on yarns available to manufacturers immediately following the war did little to allow for experimentation and developments in design. Cloth production was either plain or formed of small traditional damask patterns, and rationing was such that only so many yards could be woven so supply was limited.

1951 Festival of Britain

It was not until 1951 with the Festival of Britain (a commemoration of 100 years since the 1851 Exhibition) that designers began to experiment and introduce new ideas, which manufacturers latched onto. A Festival Pattern Group was established with the intention being that there was unity between the differing decorative arts for the Festival buildings. Designs for apparel, glass and ceramic wares, carpets, textiles and furniture were based on crystal structures. Alec Hunter and Marianne Straub produced three designs from the crystalline structures, ‘Harwell’, ‘Surrey’ and ‘Helmsley’. These were used for curtains and upholstery in The Regatta Restaurant at the festival.

Marianne Staub & Frank Davies

Woven production continued at New Mills, with the hand-woven production being much reduced as the traditional silk damasks and velvets were mostly woven to a special order. By 1958, Marianne Straub and Frank Davies were working in the studio continuing to encourage good design through commissions from art college graduates around the country. Straub and Davies’s own work for the company required the cloth to be durable, practical and, as it was for a new lifestyle, of a new pattern too. Davies designed, for the first time since the 1880s, a new cloth for The Royal Household, which was based on the architecture of Buckingham Palace rather than a repeat order for a damask. He also designed cloth using new yarns of lurex within his power weaves, where the patterning reflected the psychedelic age of the 1960s. Straub’s technical prowess showed that she understood construction, wear and flammability of cloth that was to shape the future of manufacturing to legal requirements and to be able to supply furnishing fabrics to its customers. In 1968, she produced an innovative worsted cloth for the Central Electricity Generating Board, which incorporated fine filaments of stainless steel. This acted as a conducting agent for high voltage screening suits, protecting the engineer working on electricity pylons from a fatal incident.

New Mills closure

At the start of the 1960s, the appointment of Leonard St John Tibbitts (1917-2001, Grandson of Frank Warner) was made. He had previously trained within each department of Warner & Sons, so was able to fully understand the production of a Warner cloth. Like the previous Warner men, he concerned himself with both the industrial and craft sides of the textile industry. Becoming Upper Bailiff of the Worshipful Company of Weavers, he allowed designers to be creative and encouraged collaborations with Greeff Inc. in America. He also carefully managed the transferal of the weaving business. In 1966, a subsidiary company, The Warner Weaving Company was formed to control the weaving production at New Mills, as special orders and those for Governmental offices had declined and printed fabric gained popularity. New Mills, which was only suited to weaving, became increasingly difficult to maintain, and it was then decided that the production was no longer viable. The weaving operation was gradually wound down, allowing redundant employees to find work elsewhere or to work within the warehouse. Silk weaving, which had for over a century operated on the New Mills site, ceased in 1971, with the product now being woven at several different manufacturers.

Progression with print

Eddie Squires (1940-1995) joined the design team in 1963, which was now based in both Braintree and London. He was at first responsible for all print collections, working alongside Sue Palmer to produce collections reflecting the rebirth of the Art Deco style, alongside the whimsical imagery celebrating the Lunar Landing. He became Associate Director in 1971, and his legacy of continuing to steer the design path for the company saw him engaging with new and up-and-coming talent. The firm still continued to supply The Royal Household, holding the Royal Warrant since 1932. It produced designs for P&O and their cruise liner division, as well as managing the traditional chintz cloth for the decorator customer base of Jean Monro, George Spencer, Colefax & Folwer, alongside many leading American and European wholesale fabric firms. The Arts Council’s acclaimed exhibition The Four Rooms of 1984, saw the company print ‘radical’ and technically difficult cloths for each of the show’s artists: Howard Hodgkin, Marc Camille Chaimowicz, Richard Hamilton and Anthony Caro.

The revival

In 1987, the firm became Warner Fabrics Ltd, where it expanded its product line to include accessories, wallpapers and furniture, acquiring the contract furnishing fabric firm Harris Fabrics Ltd. Through the latter part of the twentieth century, the company was sold to a variety of firms, one of which began a collaboration between Cole & Son; where the history of these two firms could marry their historic fabric and wallpaper from past decorating ventures. The design team was headed through the 1990s and early 2000s by Jo-Anne Wright, Suzannah Speller and Charles Hamer. More recently, the team comprised of freelance designers who placed their own unique style upon the brand.

In Warner’s 150th year of existence, husband and wife team Lee and Emma Clarke recognised the huge potential in this prestigious company, acquiring it in 2020. Their initial excitement was further bolstered by a greater discovery of what the firm has achieved in its long history, creating pride for the Clarkes in being able to cherish and continue in this historic tradition. They are determined that both loyal and new customers will continue to be supplied with Warner’s historic chintzes and woven cloths.